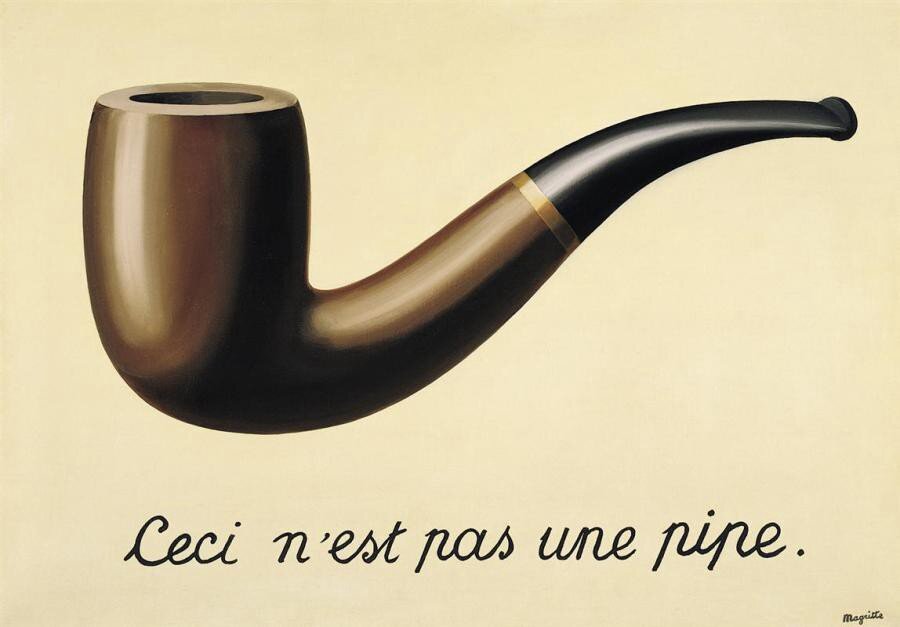

René Magritte, the great surrealist painter, liked to explore intellectual concepts through imagery. Among his more famous, and thought provoking, paintings is “This is not a Pipe:”

Magritte was unambiguous regarding the meaning of his painting:

“It’s quite simple. Who would dare pretend that the REPRESENTATION of a pipe IS a pipe? Who could possibly smoke the pipe in my painting? No one. Therefore it IS NOT A PIPE.”

I think about this painting a lot when thinking about the issue of homelessness. There are a lot of REPRESENTATIONS of homelessness in the media, most of which (in my observation) fall far short of expressing the complexity of homelessness…which is to say, they fall short of expressing the complexity of being human. There is nothing wrong with representation, just as there is nothing wrong with art. And, in fact, good art does, to paraphrase Picasso, reveal truth that is often obscured by the singular consensus vision, in which we all participate, that tends to push other visions (generally the impractical, heart based, and soulful ones) to the margins. The problem is less that we confuse the representation for the reality, when it comes to homelessness, but rather that the representations do not come from the margins…or the marginalized. They come, generally, from what we could broadly call “the establishment” (mainstream corporate news sources…those purveyors of consensus reality) even when said representations are empathetic (or at least aspire to be).

I remember seeing with great excitement, for example, a feature story about homelessness on the front page of The New York Times a few years back. Finally, I thought, the subject is getting the coverage and attention it deserves. The article had, in fact, generated a bit of buzz on social media before I read it (can’t remember for sure but I probably discovered it in someone’s Facebook feed). Unlike other articles about homelessness, as the buzz went, this piece was “literary” and presented a more poetic and artistic (and as such, more nuanced and, supposedly, human) take on the experience of homelessness.

Boy, was I disappointed. Actually, that’s putting it disingenuously mildly…I was pissed. The piece used artful turns of phrases throughout, giving it the distinct patina of being “literary,” but in straining to be artistic (and “significant” in my opinion) it stumbled into being, instead, inauthentic and inaccurate (an inexcusable sin for supposed journalism). Early in the piece, for example, the author, Andrea Elliott, describes Dasani, one of the children being profiled, as follows:

“Slipping out from her covers, the oldest girl sits at the window. On mornings like this, she can see all the way across Brooklyn to the Empire State Building, the first New York skyscraper to reach 100 floors. Her gaze always stops at that iconic temple of stone, its tip pointed celestially, its facade lit with promise.

“It makes me feel like there’s something going on out there,” says the 11-year-old girl, never one for patience.

This child of New York is always running before she walks. She likes being first — the first to be born, the first to go to school, the first to make the honor roll.”

Firstly, I grew up in New York City, I would never describe the Empire State Building as a “temple of stone.” Temple for what? And stone? There is nothing remotely stone-like about The Empire State Building, it is a distinctly sharp, non-organic and industrial structure. And lit with promise? How, exactly, do the lights of the Empire State Building suggest “promise?” Elliott is being literary for its own sake, which strikes me as amateurish and, frankly, egocentric. The whole piece reads like someone trying to impress, not describe. Even worse, this kind of self-conscious (and, again, inaccurate) literariness is directed at human being, Dasani; her gaze ALWAYS stops at the Empire State Building? She is NEVER one for patience? She is ALWAYS running? Likes being first…to be born?

Come on.

This is so over the top in an effort to be, I don’t know, poetic maybe(?), that it does a disservice to Dasani by directing the reader’s attention to the writing (and, by extension, the writer) rather than the young girl who is, ostensibly, the focus of the exposé.

Later in the article she describes a part of New York I know even better than the Empire State Building, LaGuardia Arts (where I, in fact, went to High School), and she is even more wildly off base in her description of my alma mater:

“Housed in a faded brick building two blocks from Auburn, McKinney is a poor-kids’ version of LaGuardia Arts, the elite Manhattan public school that inspired the television series “Fame.” Threadbare curtains adorn its theater. Stage props are salvaged from a nearby trash bin. Dance class is so crowded that students practice in intervals.”

Elliott is attempting to present this kind of “Tale of Two Cities” contrast between haves and have-nots, in comparing McKinney to LaGuardia. There is only one problem: as a PUBLIC school, Laguardia is, in fact not the least bit elite. Like all pubic schools there is no tuition — entrance is entirely based on merit. My father was poor and my mother was, in fact, living on the streets while I attended. The student body is actually largely from poor or lower-middle class backgrounds, and largely minority. Had Dasani qualified, skill and talent-wise, she would have been able to attend just like all the other students who got in. LaGuardia should have been celebrated, by Elliott, for being a great example of the best of what a true meritocracy represents, not for being “elitist” just for being in Manhattan, and famous. That’s nonsense. But that accurate portrayal would not have served her self-conscious literary construct, so accuracy be damned.

Worse than Elliott’s over the top amateurish writing and inaccurate reporting is the ideology of intolerance being delivered to the reader via the trojan horse of grandiose faux-poetic portraiture and activist rhetoric. Putting it more succinctly, it is classic neoliberalism. The piece, which was published in 2013, echoes a lot of the language that had entered the public discourse on the heals of the Occupy movement. Elliot writes, for example, the following early on in the article:

“Long before Mayor-elect Bill de Blasio rose to power by denouncing the city’s inequality, children like Dasani were being pushed further into the margins, and not just in New York. Cities across the nation have become flash points of polarization, as one population has bounced back from the recession while another continues to struggle. One in five American children is now living in poverty, giving the United States the highest child poverty rate of any developed nation except for Romania.

This bodes poorly for the future. Decades of research have shown the staggering societal costs of children in poverty. They grow up with less education and lower earning power. They are more likely to have drug addiction, psychological trauma and disease, or wind up in prison.”

This sure seems a pretty progressive “Occupy-esque” analysis. The problem is that such systemic rebukes are repeatedly undermined by her description of Dasani’s parents, who are, along with Dasani, the primary focus of the article. Case in point:

“Dasani’s circumstances are largely the outcome of parental dysfunction. While nearly one-third of New York’s homeless children are supported by a working adult, her mother and father are unemployed, have a history of arrests and are battling drug addiction.”

Again, this victim-blaming is somewhat (at least on the surface) neutralized by the following passage:

“Yet Dasani’s trials are not solely of her parents’ making. They are also the result of decisions made a world away, in the marble confines of City Hall.”

The key is to recognize where Elliot is putting the emphasis and, by extension, the bulk of the blame: LARGELY on the parents so-called dysfunction (arrests and addiction) but not SOLELY. In other words, yeah, the system is broken, but the blame for Dasani’s challenging condition lies mainly at the feet of her parents (a classic stereotypical trope about minorities and the poor). To be clear, this is not an isolated account, it is a repeated motif. In writing about the importance of well run and well funder schools, Elliott writes, for example:

“For children like Dasani, school is not just a place to cultivate a hungry mind. It is a refuge. The right school can provide routine, nourishment and the guiding hand of responsible adults.”

While Dasani’s parents are not mentioned by name, the subtext, that Dasani’s parents are irresponsible, is clear. Here are several more examples of Elliott blaming Dasani’s parents (and reinforcing the stereotype):

“She [Dasani] likes being small because “I can slip through things.” In the blur of her city’s crowded streets, she is just another face. What people do not see is a homeless girl whose mother succumbed to crack more than once, whose father went to prison for selling drugs, and whose cousins and aunts have become the anonymous casualties of gang shootings, AIDS and domestic violence.”

“After-school resources have thinned, but not the needs of students whose families are torn apart by gun violence and drug use.”

“Perhaps it is no accident that amid the bedlam of Dasani’s home life — the missed welfare appointments and piles of unwashed clothes — she is drawn to a craft of discipline.”

The article is littered with large, detailed photographs that further reinforce Elliott’s stereotypical narrative:

When Elliott does write about inequality it is usually couched in very partisan language, another attribute of neoliberalism. Mayor Bloomberg, the Republic Mayor of New York during the ’08 crash, for example, is repeatedly singled out for advancing policies that exacerbated inequality:

In 2011, Mr. Bloomberg ended Advantage after the state withdrew its funding. Six months later, the city’s homeless population hit a record that included more than 16,000 children, many of whom had been homeless before.

With the economy growing in 2004, the Bloomberg administration adopted sweeping new policies intended to push the homeless to become more self-reliant. They would no longer get priority access to public housing and other programs, but would receive short-term help with rent. Poor people would be empowered, the mayor argued, and homelessness would decline.

By contrast, despite the fact that Democrats have largely advanced similarly draconian “austerity” policies over the past couple of decades, they are consistently painted by Elliott as heroes and savior figures, as in this description about Bill Clinton:

“Joanie turned her life around after President Bill Clinton signed legislation in 1996 to end “welfare as we know it,” placing time limits and work restrictions on recipients of government aid. She got clean and joined a welfare-to-work program, landing a $22,000-a-year job cleaning subway cars for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. “This is the happiest day of my life,” she told Chanel.”

So, oddly, Clinton’s social safety net cutbacks, according to Elliott, benefitted the poor, whereas Bloomberg’s didn’t. Later she describes a poster hanging on the wall of Dasani’s school:

“A poster across the hall depicts a black man in sagging jeans standing before the White House, opposite President Obama. “To live in this crib,” the poster reads, “you have to look the part.”’

Message: it’s through taking personal responsibility that one rises above one’s circumstances. No mention, however, anywhere in the article that Obama bailed out Wall Street but offered no relief to homeowners who were victimized by the subprime mortgage scandal that left many, principally African Americans (who were specifically targeted by the banking industry), without a home and, by extension, on the streets. No mention, either, about Obama admitting to having used drugs yet doing nothing to curb the war on drugs, in which minorities have been disproportionately incarcerated even though whites and blacks use drugs at the same rate. The poster, visually, is also subtly racist in its tropes, with Obama being (as Joe Biden would describe him) “clean” looking, and light skinned, as compared to the “irresponsible” character on the poster who is noticeably darker:

This is not homelessness, folks.

To be completely fair, and accurate, it a REPRESENTATION (ala Magritte’s pipe) of homelessness…as seen through the lens of elitism. In the same way that the Ku Klux Klan is Christianity as filtered through the lens of white supremacy. This may seem like a harsh comparison, and on the surface perhaps it is. After all, Elliott’s article did, to her credit, reveal the hellish conditions in New York’s city run service facilities, and the Mayor’s office did make changes, including the removal of 400 children from the city’s worst shelters, to improve conditions for many of the most vulnerable victims of systemic inequity [citation].

Beneath the surface, however, despite leading to short-term systemic improvements, what Elliott’s article represents poses a deeper threat to the vulnerable because it maintains, and validates, a system wherein the voices of the marginalized are filtered through a representative (and defender) of a privileged elite status quo, one in which dangerous stereotypes are reinforced and the deep systemic roots of poverty and homelessness, such as war, climate change, racism, and income inequality, are rarely exposed, and in fact are often promoted, while critics of the system are actively silenced [citation: FAIR].

Contrast that NY Times article with a beautiful piece called “Sviatoslav Richter” by writer David Means recently in the New Yorker on the subject of homelessness. In the piece, Means’ vivid portrait of a homeless man is a starting point for a deeper exploration of self and culture, as illustrated by the following passage:

“The way he roots through the garbage cans in the winter snow and in the summer heat with an admirable persistence serves as a touchstone, fueled by the concept of mental illness afloat over the land, even, say, for the less educated observers who just see him and think, Fucking crazy old homeless bastard hanging in there, still going, still doing his thing. The phrase “mental illness” shrouds his body as he walks, and orients him, slips him like a peg into whatever dreamy ideas of madness fill the minds of those passing and pushes away the thought that he is, in a way, say, a reflection of some part of themselves that might, someday, under the right circumstances—a financial loss leading to ruin, say, or some neurological disorder, an improper linking of nerves, or a shady haze of undetected tumor, or some sharp trauma abrupt enough to throw off their general balance—irrevocably force them into the same circumstances, wandering day after day, sticking to the same general pattern, stopping to dig in the public trash can for discarded bottles or scraps of food or newspapers to read.”

Means, here, is not only brilliantly exposing the fragile line that exists between the so-called “crazy” and the supposed sane, (and surfacing fears about said fragility that exist in all of us) but also adroitly pointing out how the “mental illness” paradigm, which is the predominant cultural narrative for understanding people like the man at the center of Means’ story, obscures this fragility and amplifies the illusion of distinct separation between the so-called “crazy” and the supposed sane. While a piece of fiction, Means, in the vain of Picasso’s famous observation that art is the lie that reveals the truth, peals away in one paragraph aspects of “otherness” and “otherizing” that Elliott doesn’t come close to exposing (and, in fact, exacerbates through her old-school “anthropological” approach) in her much ballyhooed gazillion-word exposé about homelessness.

This critique would be irrelevant if Means, and other similarly keen observers and powerful writers, were given equal exposure as compared to writers like Elliott. But the New York Times, along with a handful of other institutions, garner much more exposure (5x the online traffic as compared to The New Yorker) and are granted elevated status as narrative spinners in our society, and so the way they frame reality carries much more weight, and has a much deeper impact on public perception (and ultimately public policy). One of the most historically tragic examples of this is how Judith Miller’s coverage in The New York Times of the WMD issue prior to the Iraq War helped sell (and seal) the neocon pro-invasion narrative, whereas Seymour Hersch, while writing for the New Yorker, powerfully (and accurately) debunked the WMD argument but was largely ignored by the corporate media echo chamber.

https://www.mintpressnews.com/u-s-media-repeats-iraq-wmd-folly-with-syria/188382/

A more recent example of contrasting news coverage illustrates how The New York Times is not only perceived to be the “paper of record,” but actively presents itself as such. There were rumblings of concern, During the 2016 Democratic primaries, that exit poll results were suggesting possible election fraud in favor of Hillary Clinton. The basis for the concern was that Clinton consistently outperformed the exit polls, as compared to her opponent Bernie Sanders, in an overwhelming majority of primaries, which some analysts determined was statistically impossible without the vote count having been manipulated. In the midst of this firestorm, The Times published an article, boldly titled “Exit Polls, and Why the Primary Was Not Stolen From Bernie Sanders” by Nate Cohn that mockingly called these concerns a “conspiracy theory.” The primary argument Cohn used in pushing back against election fraud allegations was his contention that exit polls have been inaccurate for many years, therefor they can’t be used as a barometer for gauging the accuracy of election results. The primary flaw in his reasoning is his assumption that the discrepancies between the election results and the exit polls MUST be an indication of exit poll inaccuracies, and not a possible indication of broad, ongoing issues with the voting machines. Implicit in his analysis is an establishment bias, meaning Cohn can’t even entertain the possibility of systemic flaws, possibly even fraud. This is especially troubling given that the exit poll discrepancies started when electronic voting machines were introduced, replacing historically accurate (and harder to hack) paper ballot machines. Also implicit in his analysis is the notion that fraud by establishment candidates like Hillary Clinton is outside the New York Times’ overton window of acceptable possibilities.

The contrasting opinion was presented in an article by CounterPunch, a progressive indie publication that was among a handful smeared, without a trace of evidence, by The Washington Post (one of the other top tier establishment publications) as Russian propaganda. While the analysis put forth by the author, Doug Johnson Hatlem, was much more impressively comprehensive (unlike Cohn, Hatlem went through the data with a fine toothed comb), the conclusion drawn in the CounterPunch article was much more professionally cautious:

“In short, none of these theories show strong explanatory power or correlation with the states where exit polling has missed against where it has gotten things right. The simplest answer is that exit polls not involving George W. Bush or Hillary Clinton tend to be quite accurate; ones that involve them are likely to be terrible.

But just because the available non-fraudulent explanations don’t seem to work, we are not automatically left to conclude that fraudulent explanations are the only way to go. Perhaps someone will come up with a new, non-fraudulent explanation that works.”

We have, as such, publications “of record” like the Times and WaPo routinely using shoddy journalism and establishment bias to spin the cultural narrative on crucial topics like homelessness, poverty, race, war, and politics, while more nuanced and accurate takes on these subjects are relegated to the fringes, and often actively dismissed by the establishment “truth” purveyors. The result is, of course, tragic. Powerful people and systems go unchecked while marginal members of the community, foreign and domestic, are misrepresented or underrepresented, leading to endless military and political aggression towards vulnerable populations. Not exactly a recipe for a healthy democracy and a merciful and just society.

…

*According to the New York Times and other mainstream news outlets that propagate stereotypes about homelessness, this is not a homeless person…but, in fact, it is. Meet Jim, one of the guests at a North London shelter photographed by artist Rosie Holtom in her series “Shelter from the Storm.” Holtom challenges misperceptions and prejudices with her intimate and humane portraits of the Zarim. See more of her terrific work at rosieholtom.com